Most of us know what a butterfly looks like. You see one in your garden, and you can immediately identify it as a butterfly. But do you know all there is to know about butterfly anatomy? Do you know what makes a butterfly a butterfly?

You might look at a butterfly and quickly (but wrongly) assume it is just a body with a couple of wings attached. But there is an awful lot more going on. Let’s break down the complete anatomy of a butterfly:

External Anatomy

Starting with what you can see as a casual observer is a great place to start so let’s first take a look at the external anatomy of a butterfly:

Wings

Butterflies, members of the order Lepidoptera, are perhaps best known for their stunning wings, which captivate observers with their intricate patterns and vibrant colors. But there’s more to these wings than meets the eye.

Structure and Composition

A butterfly’s wing comprises thin layers of a protein called chitin. This is the same protein that makes up the exoskeleton of other insects.

These layers are supported by a network of veins, which provide rigidity and contain the butterfly’s hemolymph (equivalent to blood in vertebrates).

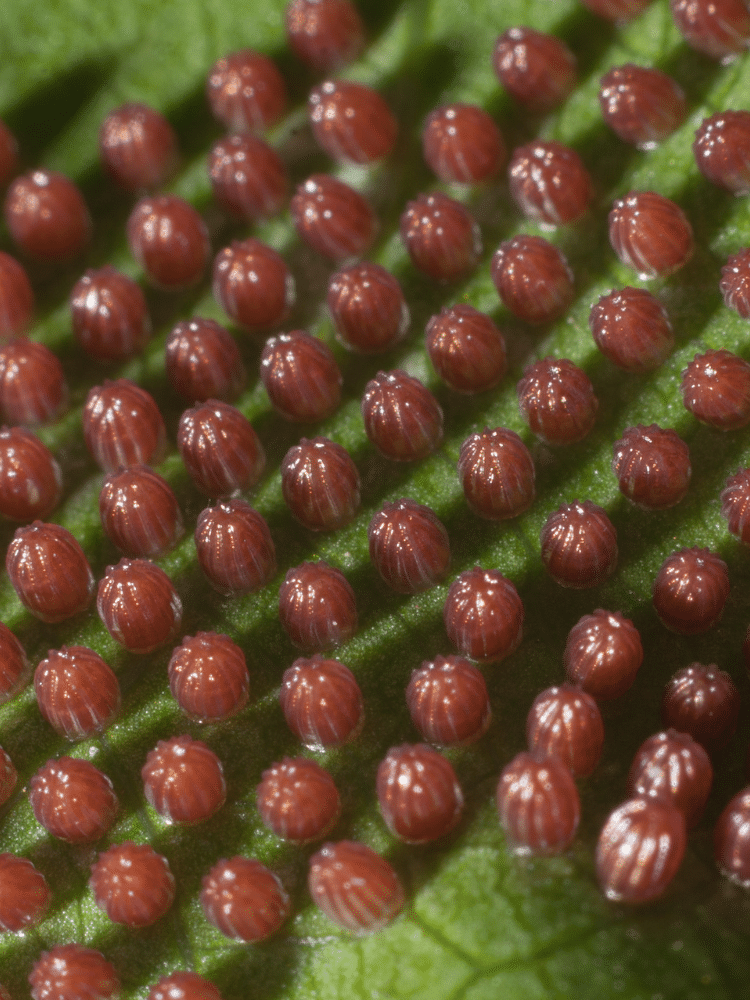

The wings are covered in thousands of tiny scales overlapping like shingles on a roof. These scales, which are pigmented or structured in ways that reflect light, are responsible for the vibrant colors and symmetrical patterns we see.

Wings

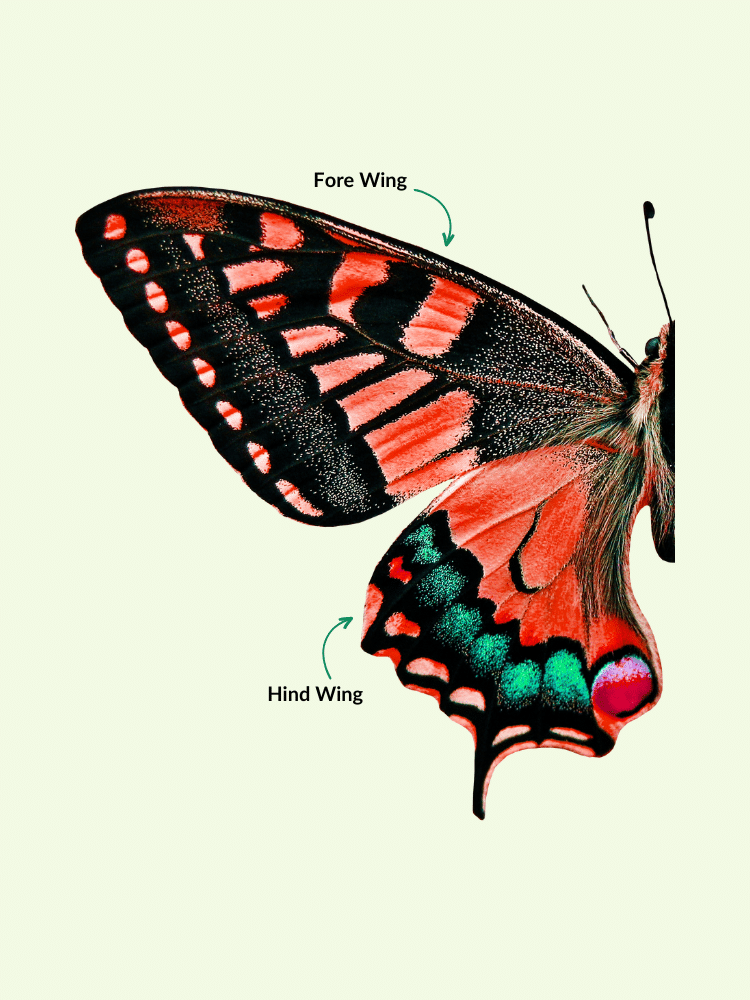

Butterflies have two pairs of wings: the forewings and the hindwings.

The forewings are typically more triangular and closer to the butterfly’s head, while the hindwings are often more rounded or scalloped. The hindwings are crucial in steering during flight, while the forewings provide power.

Scales and Color

The colors and patterns on a butterfly’s wings are not just for show. They serve essential functions like camouflage, mate attraction, and warning predators of toxicity.

The colors come from two primary sources: pigments and structural colors.

Pigments are molecules that absorb specific wavelengths of light and reflect others. For instance, melanin provides black or brown colors. On the other hand, structural colors are created when light interacts with the microscopic structure of the scales.

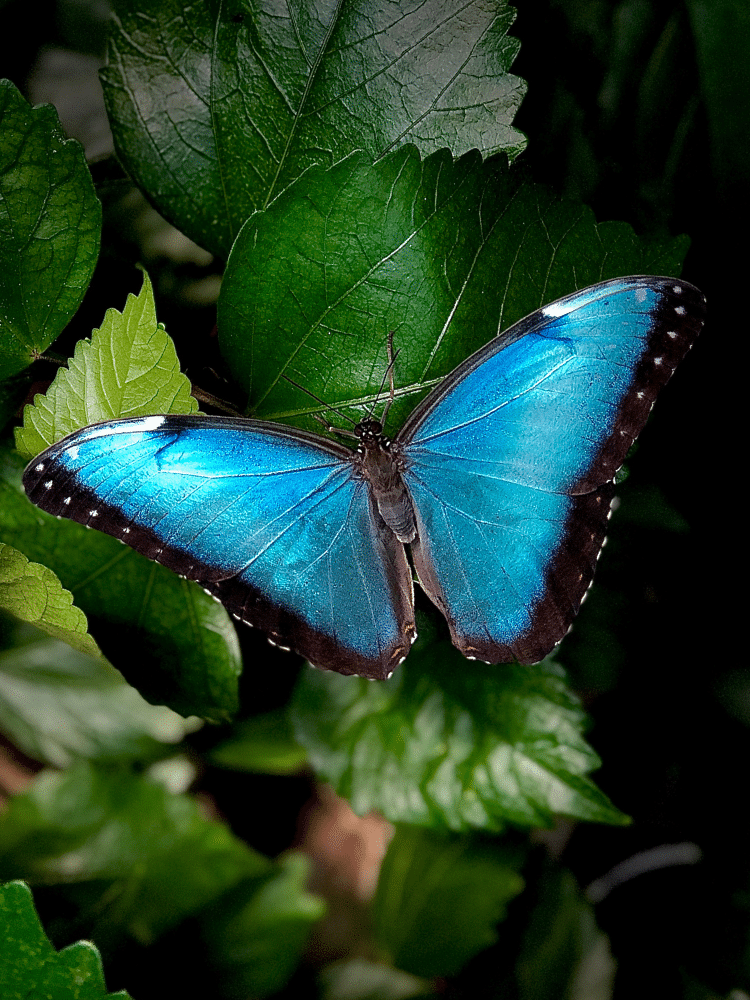

The iridescent blue of the Blue Morpho butterfly, for example, isn’t due to pigments but is a result of light refracting off the microscopic structures of its scales.

Butterfly Wings are Repairable

While a butterfly can’t regenerate a lost or severely damaged wing, minor tears can be “repaired” using scales from other parts of the wing, ensuring they can still fly effectively.

In essence, a butterfly’s wings, while delicate to the touch, are marvels of nature, combining form and function beautifully and efficiently.

Head

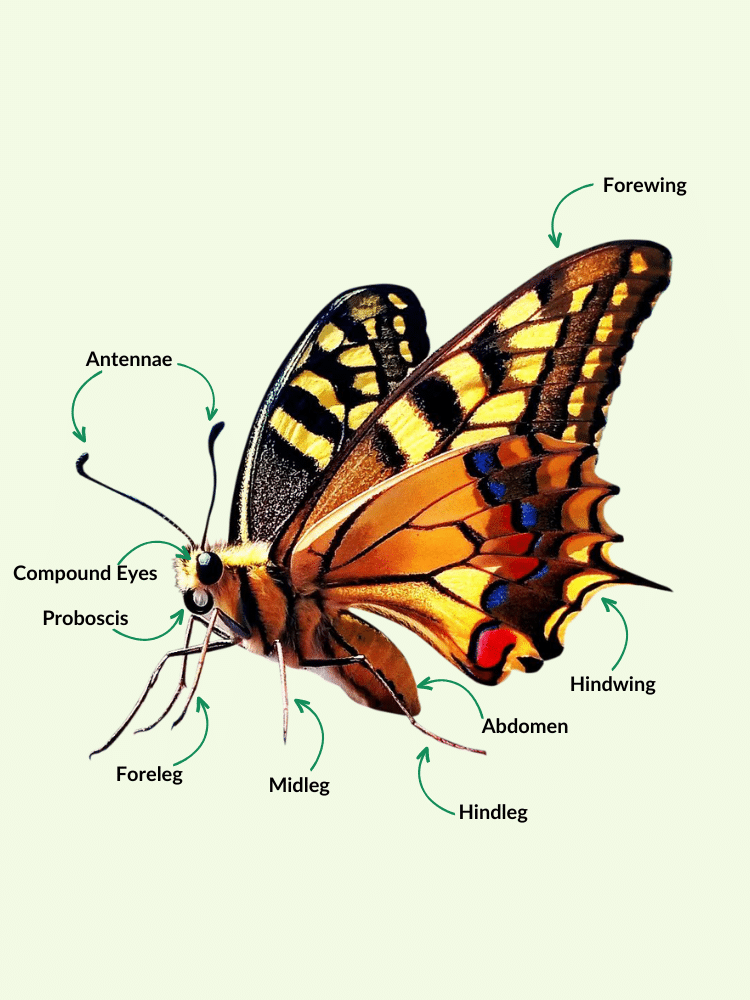

The head of a butterfly, though small in comparison to its vibrant wings, is a hub of sensory activity and vital functions. It houses the primary sensory organs, allowing the butterfly to interact with its environment, find food, and communicate with potential mates.

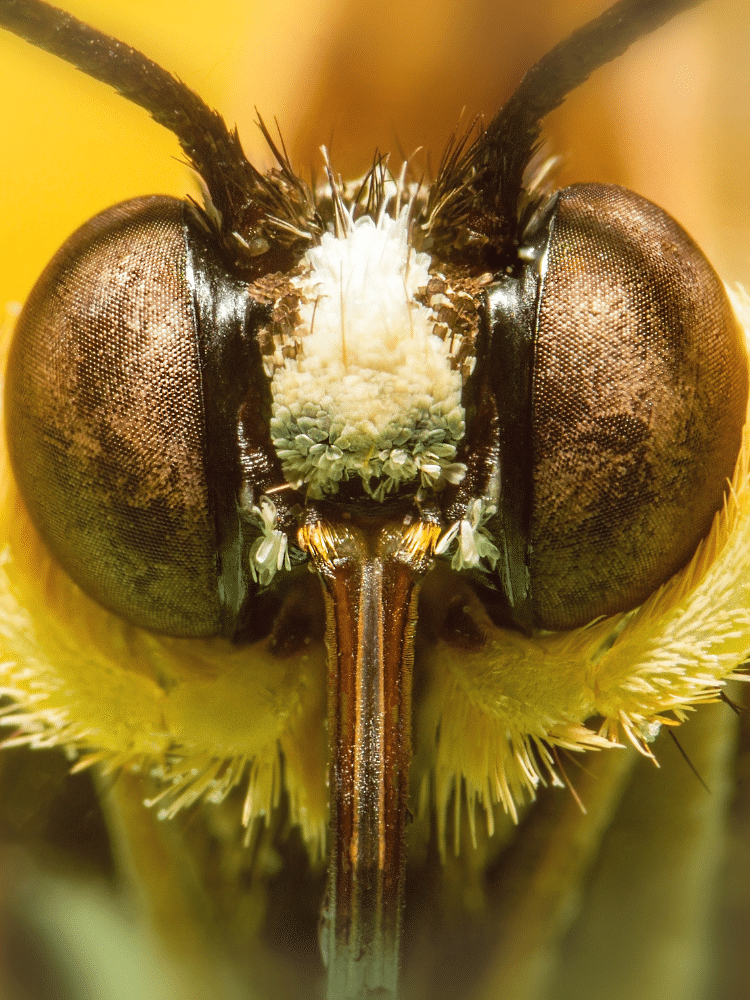

Eyes

Butterflies possess two large compound eyes, consisting of thousands of individual lenses called ommatidia. Each ommatidium captures a tiny fragment of the butterfly’s surroundings, creating a mosaic image.

This structure allows butterflies to detect fast movements, crucial for evading predators.

Additionally, butterflies can see various colors, including ultraviolet light, which is invisible to humans. This ability helps them locate nectar-rich flowers and potential mates.

Apart from compound eyes, butterflies also have simple eyes or ‘ocelli.’ These are not used for forming images but detect changes in light intensity, aiding in circadian rhythms and orientation.

Antennae

A butterfly’s antennae are its primary olfactory organs, sensitive to various chemical signals. They can detect pheromones released by potential mates, even from great distances.

Additionally, the antennae play a role in navigation, helping butterflies maintain their direction during a flight. Contrary to popular belief, the antennae are not used for hearing; butterflies sense sound through their wings and body as they do not have ears.

Proboscis

One of the most fascinating features of a butterfly’s head is the proboscis. It’s a long, coiled tube for feeding like a straw. When not in use, the proboscis remains coiled close to the head.

When a butterfly finds a nectar-rich flower, it unfurls the proboscis, inserting it into the flower to drink. This specialized structure allows butterflies to feed on liquid nutrients, primarily nectar, but also the juices from rotting fruits and, in some species, even tree sap or animal tears (no, really!).

Compound Eyes Aid Migration

Some species, like the Monarch butterfly, undertake vast migrations. Researchers believe that their compound eyes play a crucial role in this, helping them use the position of the sun as a compass.

While compact, the head of a butterfly is a marvel of evolutionary adaptation, ensuring the insect can find food, mates, and navigate its colorful world with precision.

Thorax

The thorax is the powerhouse of the butterfly, housing the muscles that power its wings and legs. It’s the central segment of the insect’s body, connecting the head to the abdomen, and plays a pivotal role in locomotion and sensory perception.

Muscles and Movement

The thorax contains the flight muscles, which are among the most powerful in the insect world relative to their size. These muscles attach to the base of the wings and contract rapidly, allowing the butterfly to flutter or glide.

The up-and-down movement of the wings is achieved by alternating contractions of two primary sets of muscles: the dorsoventral muscles and the longitudinal muscles.

The intricate coordination of these muscles gives butterflies their characteristic flight patterns, from the rapid fluttering of skippers to the graceful glides of swallowtails.

Legs

Butterflies have three pairs of legs, each attached to a segment of the thorax. These legs are not just for walking; they’re also essential sensory organs. Equipped with chemoreceptors, especially on the feet (tarsi), they allow the butterfly to “taste” its environment.

This ability is particularly crucial for female butterflies when identifying suitable plants on which to lay their eggs.

Additionally, the legs aid in maintaining balance during flight and serve as anchors when the butterfly is feeding or resting.

4-Legged Butterflies

Some species appear to have only four legs. However, they do have six legs. The front pair is reduced in size and often curled up, giving them the common name “brush-footed butterflies.”

The thorax, with its robust muscles and sensory legs, equips the butterfly for its daily activities, from the energetic flights to the delicate process of landing on flowers and tasting the world around them.

Abdomen

The abdomen, the elongated segment trailing behind the thorax, is a vital part of the butterfly’s anatomy.

It houses several essential organs and systems, playing a crucial role in digestion, reproduction, and respiration – more on those further down as we dive into the internal anatomy of a butterfly.

While not as visually striking as the wings or as sensory-rich as the head, the abdomen is a testament to the butterfly’s evolutionary adaptability. It’s a hub of essential functions.

Internal Anatomy

Diving deeper into the butterfly’s structure, we find a complex network of systems sustaining its life, from the circulation of vital fluids to processing sensory information.

The internal anatomy of a butterfly is a marvel of evolutionary design, ensuring efficiency and survival in various environments.

Circulatory System

Unlike mammals, butterflies have an open circulatory system. This means that instead of blood flowing through closed vessels, they have a fluid called hemolymph that bathes their internal organs directly.

The heart, an elongated tube running along the abdomen’s length, pumps this hemolymph throughout the body. The hemolymph carries nutrients, removes waste, and even plays a role in thermoregulation, helping the butterfly adjust to varying temperatures.

Respiratory System

Butterflies breathe through spiracles leading to tracheae. These tracheae branch out into finer tubes called tracheoles, which deliver oxygen directly to the cells.

This direct delivery system allows for efficient oxygen exchange, crucial for the butterfly’s high-energy activities like flight.

Nervous System

The butterfly’s nervous system is centralized in the head, where the brain resides. The brain processes sensory information from the eyes, antennae, and other sensory organs.

From the brain, two nerve cords run down the length of the body, transmitting signals and controlling movements. These nerve cords have ganglia or nerve clusters, at intervals, which further aid in processing and transmitting information.

Not the Memory of a Goldfish

Recent studies suggest that butterflies have a more sophisticated memory than previously believed. Some species can remember their larval feeding grounds, aiding in their migration patterns.

Digestive System

The butterfly’s digestive system begins at the proboscis, where nectar or other liquid foods are ingested.

This food then moves to the foregut, where enzymes begin the digestion process. The midgut continues the breakdown, extracting necessary nutrients.

Any waste products are then passed to the hindgut, where water is reabsorbed, and the waste is excreted or peed out.

The butterfly’s internal anatomy, while hidden from view, is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. Every system, every organ has evolved to ensure the butterfly’s survival in its vibrant, ever-changing world.

Special Features

Butterflies, with their delicate appearance and ethereal beauty, are more than just a visual treat.

They possess a range of unique features and adaptations that have evolved over millions of years, allowing them to thrive in diverse environments and play crucial roles in ecosystems.

Scales

The word “Lepidoptera,” the order to which butterflies belong, is derived from the Greek words for “scale” and “wing.” This name is apt, as one of the most distinctive features of butterflies is the tiny scales covering their wings.

These scales, which overlap like tiles on a roof, are responsible for the myriad colors and patterns seen in butterfly wings. Each scale is a flattened outgrowth of the butterfly’s exoskeleton (butterfly bones are on the outside) and can be pigmented or can produce colors through structural mechanisms, like refraction.

Pheromone Glands

Communication is vital for butterflies, especially when it comes to finding a mate. Pheromone glands, primarily located in the abdomen, produce chemical signals that can attract potential mates from a distance.

Each species has its unique pheromone signature, ensuring that the signals don’t get mixed up in the bustling world of insect communication.

Hearing Organs

While butterflies don’t have ears like mammals, they’re not deaf. They possess specialized organs called tympanal organs that can detect sound vibrations.

Located at the base of the wings or on the thorax, these organs can sense the ultrasonic calls of hunting bats, allowing nocturnal species to take evasive action.

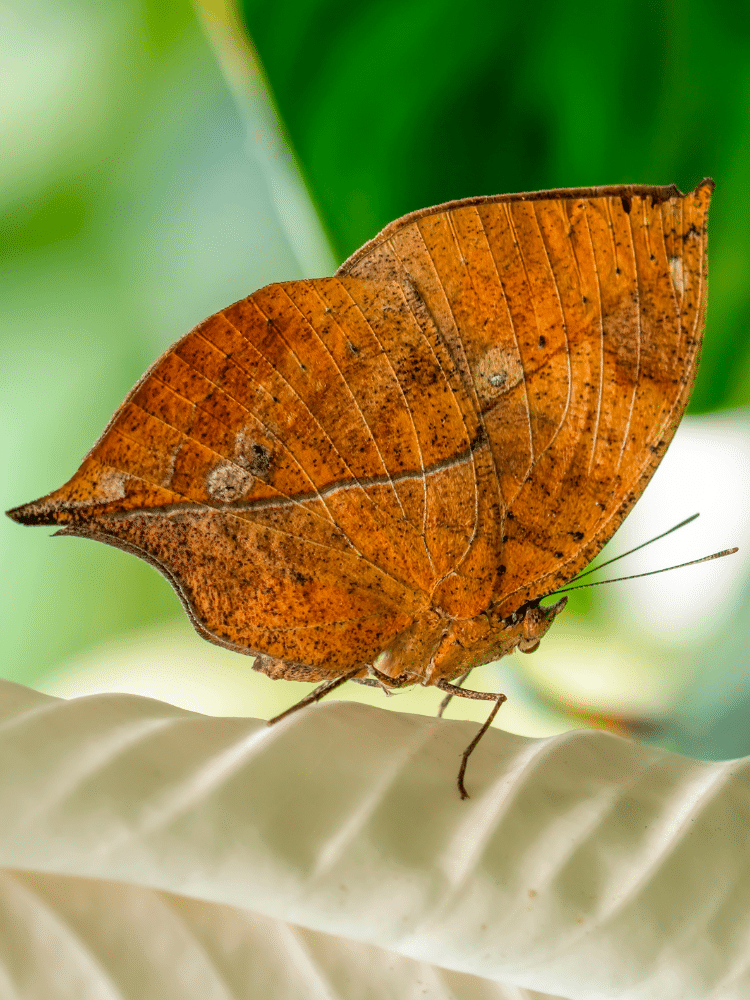

Camouflage and Mimicry

Many butterflies have evolved wing patterns that allow them to blend into their surroundings, a feature known as camouflage. This adaptation helps them avoid predators.

On the other hand, some species use mimicry, where they develop patterns resembling those of toxic species, deceiving predators into thinking they’re harmful when they’re not.

These special features highlight the incredible adaptability and evolutionary prowess of butterflies.

Each adaptation, whether for survival, reproduction, or communication, underscores the intricate dance of evolution and the delicate balance of nature.

Unique Features

While all butterflies share certain commonalities, individual species have evolved unique features that set them apart, often aiding in their survival and reproduction.

Here’s a closer look at some of these species-specific marvels:

Owl Butterfly: Eyespots

The Owl Butterfly, native to the rainforests of Central and South America, is named for the large, eye-like spots on its wings.

These eyespots serve a dual purpose: they can startle potential predators, making them think they’re facing a larger animal, and they can also divert attacks away from vital body parts, as predators might aim for the “eyes” rather than the butterfly’s body.

Swallowtail Butterfly: Tail-like Extensions

Swallowtails, found worldwide, are easily recognizable by the tail-like extensions on their hindwings, resembling the forked tail of swallows. These tails can serve as a false target for predators, directing attacks away from the butterfly’s body.

What’s That Smell?

Some Swallowtail species have a hidden surprise – when threatened, they can evert a forked, orange gland called the osmeterium from behind their head, releasing a foul-smelling secretion to deter predators.

Glasswing Butterfly: Transparent Wings

The Glasswing Butterfly, found in Central America, has wings that are almost entirely transparent.

This transparency is due to the lack of colored scales on large portions of its wings and the unique structure of its wing membranes, which prevent light scattering.

Painted Lady Butterfly: Migration

While many butterflies migrate, the Painted Lady holds the record for the longest known butterfly migration. Found across continents, this species undertakes a multi-generational migration, covering thousands of miles.

Unlike other migratory species like the Monarch, which has a set start and endpoint, the Painted Lady’s migration is more sporadic, driven by environmental conditions and availability of food sources.

Blue Morpho Butterfly: Iridescent Blue Wings

Native to the rainforests of South and Central America, the Blue Morpho is renowned for its stunning, iridescent blue wings.

This shimmering effect isn’t due to pigmentation but rather the microscopic structure of their scales, which reflect and refract light in a way that produces the vivid blue hue.

Heliconius Butterflies: Long Lifespan & Memory

Unlike most butterflies that live for only a few weeks, some Heliconius species can live up to several months. This extended lifespan is paired with a good memory, allowing them to return to the same flowers day after day.

Heliconius butterflies have a unique behavior called “pupal mating,” where males mate with females before they have even emerged from their chrysalis, ensuring that they are the first and only to mate with her.

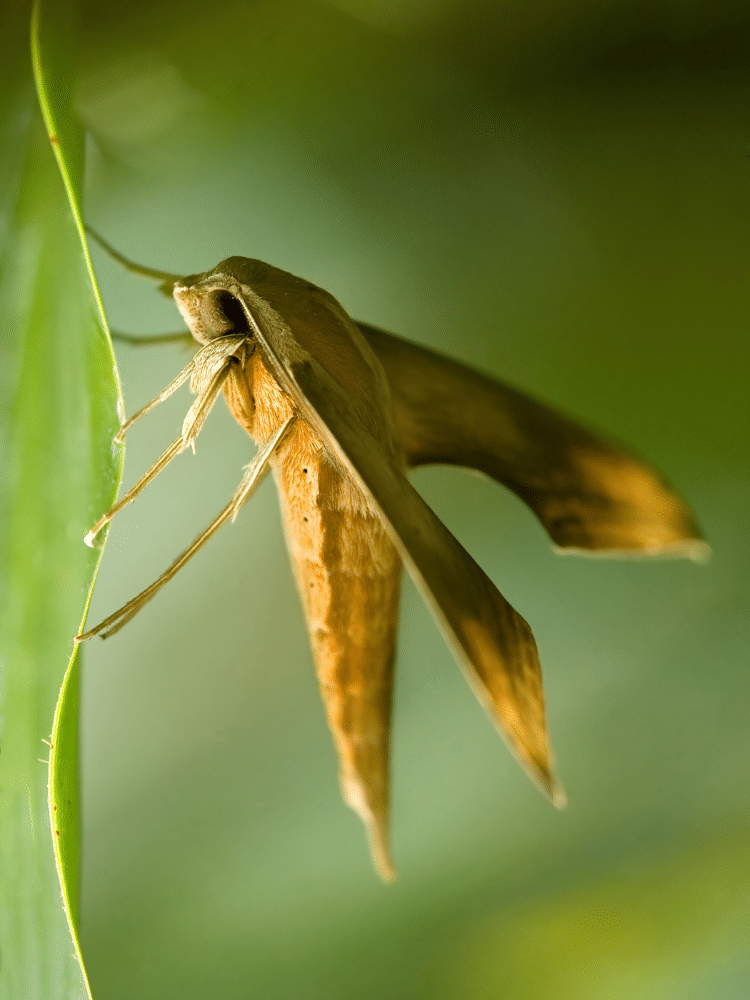

Dead Leaf Butterfly: Leaf Mimicry

Found in Asia, this butterfly has wings that closely resemble a dried, dead leaf. When its wings are closed, it shows off detailed veining, mimicking the appearance of a leaf complete with imperfections like spots and discolorations.

Each of these species, with their unique features, showcases the incredible diversity within the world of butterflies. These adaptations, honed over millennia, highlight the intricate relationship between these insects and their environment.

Defense Mechanisms

In the vast and intricate web of life, survival often hinges on the ability to avoid becoming someone else’s meal.

Butterflies, despite their delicate appearance, have evolved a range of defense mechanisms to deter or escape from predators. These strategies, both passive and active, showcase the butterfly’s adaptability and the intricate dance of evolution.

Camouflage

One of the most common defense strategies in the animal kingdom, camouflage allows butterflies to blend into their surroundings.

The Grayling Butterfly, for instance, has wings that resemble the texture and color of tree bark and stones. When it rests with its wings closed, it becomes almost indistinguishable from its backdrop. By mimicking their environment, these butterflies can effectively hide in plain sight.

Mimicry

Some butterflies don’t just blend in; they pretend to be something they’re not. This is known as mimicry.

For example, the Viceroy butterfly mimics the coloration of the toxic Monarch butterfly. Predators, having had a bad experience with a real Monarch, are likely to avoid the Viceroy, thinking it’s also toxic.

Startle Tactics

Certain butterflies have eyespots on their wings, which, when displayed suddenly, can startle and scare off potential predators.

The Buckeye Butterfly, for example, features prominent eyespots on its wings that can give pause to would-be attackers, making them reconsider their approach, especially when the butterfly is in motion.

Chemical Defenses

Some butterflies are genuinely toxic or distasteful. They accumulate toxins from the plants they consumed as caterpillars, making them unpalatable or even harmful to predators.

The Monarch butterfly, for example, ingests toxins from milkweed plants, which makes it poisonous to birds.

Osmeterium

Unique to swallowtail butterflies, the osmeterium is a forked, glandular organ that, when everted, releases a foul-smelling secretion. This stench serves as a deterrent to predators, especially when the butterfly is in its caterpillar stage.

Flight Patterns

Some butterflies have erratic flight patterns, making them hard to catch. The unpredictable movements can confuse predators, giving the butterfly a better chance to escape.

And no, butterflies do not bite as a defensive act. They do not have a mouth with teeth that would enable them to bite!

Butterfly Anatomy Summary

With their vibrant wings and delicate movement, butterflies are marvels of nature’s design.

Beneath their colorful exterior lies a complex anatomy: wings covered in intricate scales that dictate color and pattern, a head equipped with sensory organs for navigation and feeding, a thorax that powers flight, and an abdomen essential for reproduction and digestion.

Internally, they possess efficient circulation, respiration, and neural communication systems, making them perfectly adapted for their diverse environments and roles in ecosystems.